My idea – and again here I borrowed freely from Terravision – was to connect the resources of the web to the model of the planet. Terravision inspired my own WebEarth – a project that I've kept and maintained over the years, updated to the latest in Web3D technologies, but which has long since been outclassed by other fantastic efforts like Cesium. I immediately went off and began my own bit of coding, taking the supercomputer requirements of Terravision (it ran on a Silicon Graphics supercomputer probably less powerful than my new iPhone) and squeezing them into something that could get the point across on a desktop machine, on the web.

The reality of the Earthtracker in my hand, giving me the capacity to spin the globe about at will, permanently changed the way I thought about computing.

Terravision google earth lawsuit who won Pc#

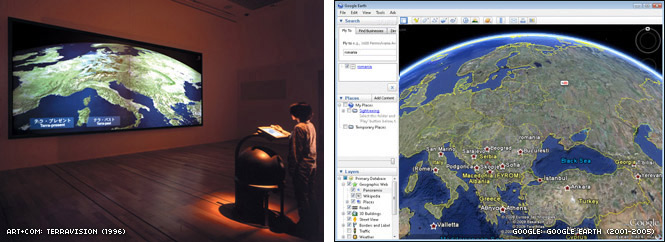

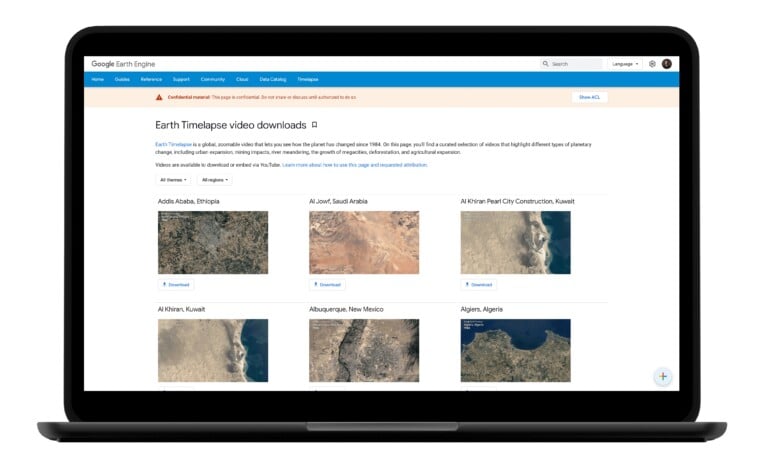

That all of this sounds exactly like the last time you fired up Google Earth on your PC or mobile became the focal point for a lawsuit filed by ART+COM against Google – and the subject of a recently released Netflix series, The Billion Dollar Code. With the press of a button on the mouse, you could dive down, from ten thousand kilometres, to a thousand, a hundred, ten, down and down, all the way to ten metres above, well, pretty much any point on Earth's surface. Using a beachball-sized trackball known as the "Earthtracker" and a "space mouse", you could interact with that visualisation freely, spinning the planet this way and that, in perfect synchrony with the Earthtracker. What good is it, really?Ĭonceived as a "whole Earth in your hands", Terravision presented a fully realised three-dimensional Earth floating space – excellent, but only the beginning.

Yet what should feel absolutely real seems exactly the opposite – leaving me cold, as though I've stumbled onto a global-scale miniature train set, built by someone with too much time on their hands. Trees resolve across successive passes from childlike lollipops into complex textured forms. Pop down inside a major city centre – Sydney, San Francisco or London – and the intense data-gathering work performed by Google's global fleet of scanning vehicles shows up in eye-popping detail.īuildings are rendered photorealistically, using the mathematics of photogrammetry to extrude three-dimensional solids from multiple two-dimensional images. That's fun, but it's not as powerful as it could be.ĭespite the fact that it often gives me a stomach-churning sense of motion sickness, I've been spending quite a bit of time lately fully immersed in Google Earth VR. Google's vision is different: it just wants you to sort of play with the world. Column I used to think technology could change the world.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)